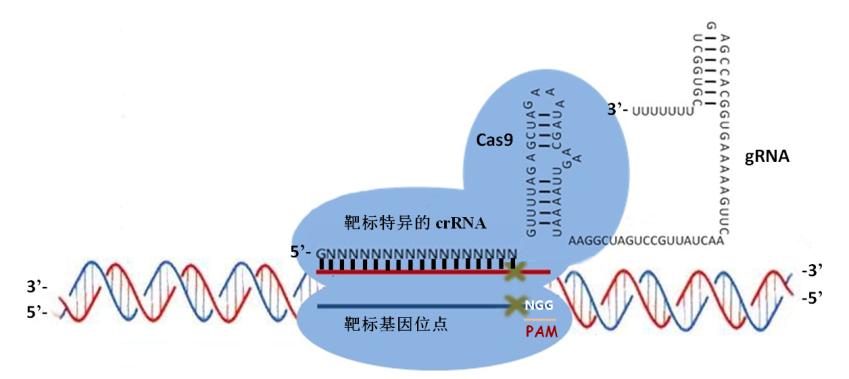

CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technology has revolutionized the field of genome modification. This system is based on two key components that form a complex: Cas9 endonuclease and a target-specific RNA (single guide RNA or sgRNA) that guides Cas9 to the genomic DNA target site. Targeting to a particular genomic locus is solely mediated by the sgRNA.

CRISPR/Cas9 简介

细菌(bacteria)和古细菌(archaea)都有一套防御机制抵御这种外来的侵入性因子,这种防御机制就是在成簇的、有规律间隔的多次重复短片段(clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat, CRISPR)的基础上建立起来的适应性免疫系统(adaptive immune system)。

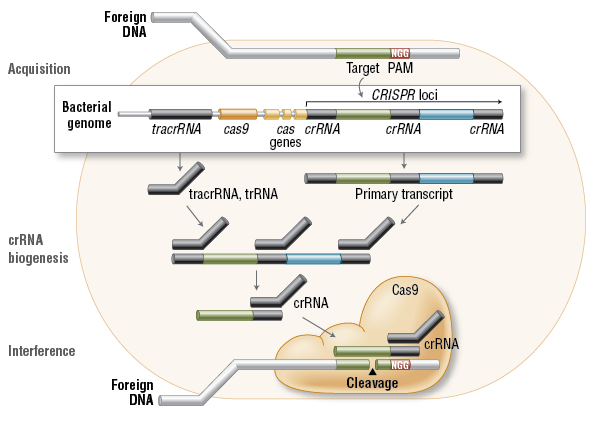

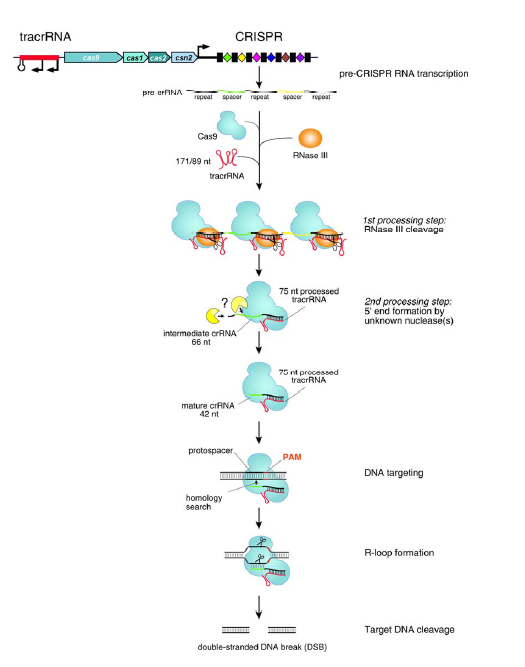

CRISPR系统能够将各种外源的病毒或质粒DNA短片段”集中”到细胞基因组里某个特定的重复片段区域上,将这些外源DNA当作细胞曾经经受过外源DNA入侵的一种记忆给储存起来。然后这段DNA会转录生成CRISPR前体RNA(precursor CRISPR RNA),前体RNA生成之后会被切割成一段一段的重复RNA片段,这些小RNA分子就是成熟的CRISPR RNA(crRNA)。然后crRNA会招募CRISPR相关蛋白(CRISPR-associated proteins, Cas)和tracrRNA与各种被细胞记住的外源的入侵DNA或mRNA片段结合,将它们彻底摧毁。

CRISPR/Cas9发现史

1987年,日本人在大肠杆菌中发现有串联间隔重复序列,后来的研究发现,这种重复序列广泛存在于细菌和古细菌中。

2002年,正式命名为CRISPR(Clustered regulatory interspaced short palindromic repeats)。

2005年,三个研究组同时发现间隔序列和侵染细菌的病毒或phage高度同源。从而推测,这一系统可能是类似于siRNA一样,是细菌抵抗Phage的一种机理。

2007年,Science发表文章,证明细菌可能利用CRSPR系统对抗噬菌体入侵,并解释细菌抵抗外界入侵的大致流程,Cas位点编码多个核酸酶和解旋酶,他们把入侵的DNA切割,整合到CRISPR的重复序列中,形成记忆。当再次遭到入侵时,转录出RNA,Cas蛋白复合物利用这些和入侵的DNA同源的RNA去切割摧毁外源的DNA。

2012年,Jennifer A. Doudna和Emmanuelle Charpentier的这篇Science发现了一个比较简单的CRISPR(TypeII)系统的机理。

CRISPR/Cas9 type II 作用机制

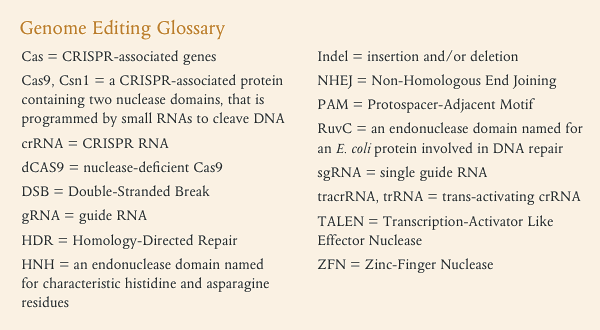

相关术语

CRISPR–Cas系统也称作2型系统(type II systems),如图所示。Cas9内切酶在向导RNA的指引下能够对各种入侵的外源DNA分子进行定点切割,不过主要识别的还是保守的间隔相邻基序(proto-spacer adjacent motifs,PAM基序)。如果要形成一个有功能的DNA切割复合体,还需要另外两个RNA分子的帮助,它们就是CRISPR RNA (crRNA)和反式作用CRISPR RNA(trans -acting CRISPR RNA, tracrRNA)。不过最近有研究发现,这两种RNA可以被”改装”成一个向导RNA(single-guide RNA, sgRNA)。tracrRNA刚好与crRNA的小片段互补,同时它们还是RNA特异性的宿主核糖核酸酶RNase III的底物。经过RNase III的切割之后,这一对互补的RNA(其中包括一条42bp的crRNA和一条75bp的tracrRNA)就可以充当Cas9因子的向导,也就是说,tracrRNA分子能够帮助Cas9-crRNA复合体在细胞复杂的DNA环境中精准地定位到入侵的DNA序列上,这个sgRNA足以帮助Cas9内切酶对DNA进行定点切割,在完整基因组上的特定位点完成切割反应后细胞通常会通过两种方式对发生双链断裂的DNA进行修复,这两种方式分别是同源重组修复机制(homologous recombination, HR)和非同源末端连接修复机制(non-homologous end joining, NHEJ),不过在修复的过程中细胞有可能会对修复位点进行修饰,或者插入新的遗传信息。

图例解释

The type II RNA-mediated CRISPR/Cas immune pathway. The expression and interference steps are represented in the drawing. The type II CRISPR/Cas loci are composed of an operon of four genes (blue) encoding the proteins Cas9, Cas1, Cas2 and Csn2, a CRISPR array consisting of a leader sequence followed by identical repeats (black rectangles) interspersed with unique genome-targeting spacers (colored diamonds) and a sequence encoding the trans-activating tracrRNA (red). Represented here is the type II CRISPR/Cas locus of S. pyogenes SF370 (Accession number NC_002737) (4). Experimentally confirmed promoters and transcriptional terminator in this locus are indicated (4). The CRISPR array is transcribed as a precursor CRISPR RNA (pre-crRNA) molecule that undergoes a maturation process specific to the type II systems (4). In S. pyogenes SF370, tracrRNA is transcribed as two primary transcripts of 171 and 89 nt in length that have complementarity to each repeat of the pre-crRNA. The first processing event involves pairing of tracrRNA to pre-crRNA, forming a duplex RNA that is recognized and cleaved by the housekeeping endoribonuclease RNase III (orange) in the presence of the Cas9 protein. RNase III-mediated cleavage of the duplex RNA generates a 75-nt processed tracrRNA and a 66-nt intermediate crRNAs consisting of a central region containing a sequence of one spacer, flanked by portions of the repeat sequence. A second processing event, mediated by unknown ribonuclease(s), leads to the formation of mature crRNAs of 39 to 42 nt in length consisting of 5’-terminal spacer-derived guide sequence and repeat-derived 3’-terminal sequence. Following the first and second processing events, mature tracrRNA remains paired to the mature crRNAs and bound to the Cas9 protein. In this ternary complex, the dual tracrRNA:crRNA structure acts as guide RNA that directs the endonuclease Cas9 to the cognate target DNA. Target recognition by the Cas9-tracrRNA:crRNA complex is initiated by scanning the invading DNA molecule for homology between the protospacer sequence in the target DNA and the spacer-derived sequence in the crRNA. In addition to the DNA protospacer-crRNA spacer complementarity, DNA targeting requires the presence of a short motif (NGG, where N can be any nucleotide) adjacent to the protospacer (protospacer adjacent motif - PAM). Following pairing between the dual-RNA and the protospacer sequence, an R-loop is formed and Cas9 subsequently introduces a double-stranded break (DSB) in the DNA. Cleavage of target DNA by Cas9 requires two catalytic domains in the protein. At a specific site relative to the PAM, the HNH domain cleaves the complementary strand of the DNA while the RuvC-like domain cleaves the noncomplementary strand.

关键点注释

1 | 5端是来源于spacer的序列,3端是来源于重复端(repeat)的序列,二者共同组成了39到42nt的成熟crRNAs,其中的3端重复端部分序列 |

1

2

3

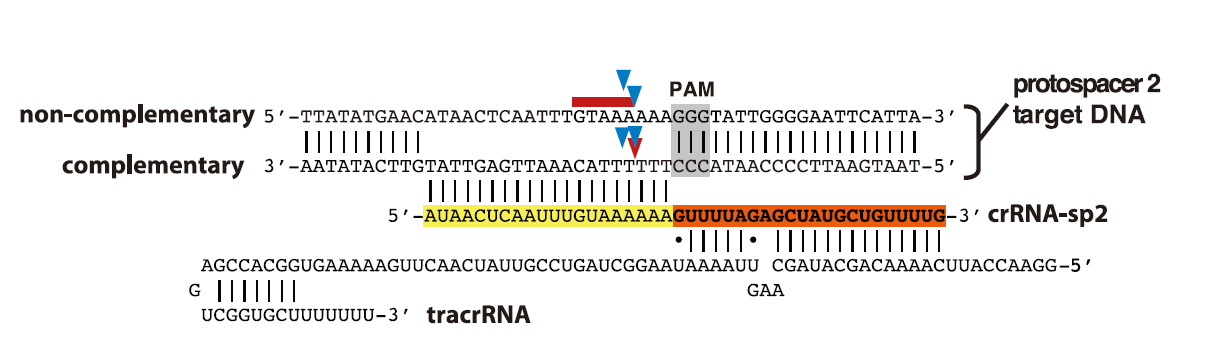

4Schematic representation of tracrRNA, crRNA-sp2, and protospacer 2 DNA sequences. Regions of crRNA

complementarity to tracrRNA (orange) and the protospacer DNA (yellow) are represented. The PAM

sequence is shown in gray; cleavage sites mapped in (C)and (D) are represented by blue arrows (C),

a red arrow [(D), complementary strand], and a red line [(D), noncomplementary strand].

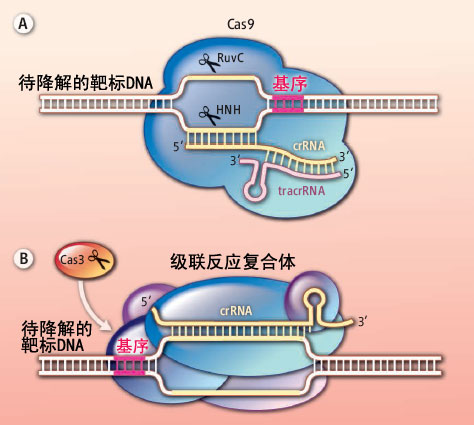

(A)Cas9蛋白需要crRNA和tracrRNA的共同帮助才能识别入侵的外来DNA分子,与之结合并将其降解。因为crRNA中的向导链部分可以与外源DNA的一条链互补并结合形成R环结构。在被识别区域两端的DNA基序也起到了非常重要的作用,它们可以帮助DNA链结旋打开双链,有利于crRNA链侵入。然后靶标DNA会在Cas9蛋白两个核酶结构域的作用下被切断。(B)级联反应复合体里含有一个crRNA,可是却最多携带了5种不同的Cas蛋白。所以它能够持续不断地招募核酶和解旋酶Cas3蛋白,不停歇地将入侵的外源DNA打开并切断。

Cas9蛋白能够凭借分子内的两个核酸酶结构域切割靶标DNA分子,形成平末端产物,其中每一个结构域负责切割靶标DNA分子R环状(R-loop)结构中的一条DNA链,具体来说,就是一个HNH核酶结构域负责切割与crRNA互补配对的那一条DNA链,RuvC核酶结构域负责切割另外一条DNA链。Jinek等人发现这种切割的效率非常高,而且不论靶标DNA分子是松弛型的,还是紧密的超螺旋型的都可以被毫不费力地被切割开,说明Cas9蛋白在细胞里是循环使用的,这样能保证在第一时间将所有来犯的入侵者全都消灭掉。

Choosing a Target Sequence for CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing

CRISPR/Cas9 gene targeting requires a custom single guide RNA (sgRNA) that contains a targeting sequence (crRNA sequence) and a Cas9 nuclease-recruiting sequence (tracrRNA). The crRNA region (shown in red below) is a 20-nucleotide sequence that is homologous to a region in your gene of interest and will direct Cas9 nuclease activity.

Selecting an appropriate DNA target sequence

Use the following guidelines to select a genomic DNA region that corresponds to the crRNA sequence of the sgRNA:

The 3′ end of the DNA target sequence must have a proto-spacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence (5′-NGG-3′). The 20 nucleotides upstream of the PAM sequence will be your targeting sequence (crRNA) and Cas9 nuclease will cleave approximately 3 bases upstream of the PAM.

The PAM sequence itself is absolutely required for cleavage, but it is NOT part of the sgRNA sequence and therefore should not be included in the sgRNA.

The target sequence can be on either DNA strand.

There are online tools (e.g., http://crispr.mit.edu/ or https://chopchop.rc.fas.harvard.edu/) that detect PAM sequences and list possible crRNA sequences within a specific DNA region. These algorithms also predict off-target effects in different organisms, allowing you to choose the most specific crRNA.

CRISPR/Cas9-sgRNA设计工具

模式生物(Model Organism)

- http://www.e-crisp.org/E-CRISP/ currently the best online solution (Recommended).

- http://tools.flycrispr.molbio.wisc.edu/targetFinder/ a simple drosophila focused tool.

- http://crispr.mit.edu/ MIT’s online CRISPR tool is a little slow, but pretty decent if they support your genome of interest.

- http://crispr.u-psud.fr/ simple but effective, supports analysis of any sequence for target-sites.

- http://zifit.partners.org/ZiFiT/ another simple but effective solution.

模式生物+部分非模式生物(Model Organism AND Some non-model organisms)

- https://crispr.dbcls.jp/ Rational design of CRISPR/Cas target.

- http://www.rgenome.net/cas-offinder/ select genomes only, but allows for alternative Cas9 species.

- http://tools.flycrispr.molbio.wisc.edu/targetFinder/ a simple drosophila focused tool.

- https://code.google.com/p/ssfinder/ (SSFinder) a simple but effective tool, it will likely be slow for large genomes.

- CasFinder: Flexible algorithm for identifying specific Cas9 targets in genomes

- http://crispr.hzau.edu.cn/CRISPR2/help.php

可自己提供基因组的程序(use yourself genome data)

- Cas-Designer: provides all possible RGEN targets in the given input sequence

- sgRNAcas9: A software package for designing CRISPR sgRNA and evaluating potential off-target cleavagesites

CRISPR/Cas9存在的问题暨避免措施

Predicting sgRNA Efficacy

We have recently examined sequence features that enhance on-target activity of sgRNAs by creating all possible sgRNAs for a panel of genes and assessing, by flow cytometry, which sequences led to complete protein knockout (1). Some sequences worked better than others, and we also saw that variations in the protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM) led to differences in activity: specifically, CGGT tended to serve as a better PAM than the canonical NGG sequence. By examining the nucleotide features of the most-active sgRNAs from a set of 1,841 sgRNAs, we derived scoring rules and built a website implementation of these rules to design sgRNAs against genes of interest, available here: http://www.broadinstitute.org/rnai/public/analysis-tools/sgrna-design.

Once sgRNA sequences most-likely to give high activity are identified, some filtering can be used to further winnow down a list. For example, basic features of the target gene can be used to eliminate some sgRNAs, such as those that target near the C’ terminus of a protein, as frameshifts are less-likely to be deleterious if most of the protein has already been translated. While every protein will be different, it seems reasonable that target sites in the first half of a protein will likely lead to a functional knockout. Indeed, for some of the genes we examined, even targets very close to the C’ terminus disrupted expression. Certainly, for any gene of interest, it would be unwise to make conclusions on the basis of the activity of a single sgRNA, and thus diversity of target sites across a gene should be examined.

Avoiding Off-target Sites

The off-target activity of sgRNAs is important to consider. Several papers have reached far-different conclusions regarding the extent of these effects, and certainly at least one reason for these observed differences is the expression levels of Cas9 and sgRNA used in these studies (2,3). Additionally, the ability to predict off-target sites in the genome is still in its infancy. While the basic landscape of mismatches that can lead to cutting has been established, and can be used to identify sites that are likely to give rise to an off-target effect, as yet there is not enough data to fully predict which sites will and will not show appreciable levels of modification. To further confound matters, it has recently been shown that bulges in either the RNA or DNA – that is, non-symmetrical basepairing of the strands – can give rise to off-target activity (4). Predicting such basepairing interactions is far-more computationally intensive, and thus existing algorithms ignore these potential off-target sites.

Importantly, recent whole-genome sequencing of cells modified by CRISPR indicates that the consequences of off-target activity, at least for the experimental conditions used, led to no detectable mutations (5). Indeed, when working with single-cell clones, the authors note that “clonal heterogeneity may represent a more serious obstacle to the generation of truly isogenic cell lines than nuclease-mediated off-target effects.” Further, several genetic screens using genome-wide libraries have shown high concordance between different sequences targeting the same gene, suggesting that off-target effects did not overwhelm true signal in these assays (6-8). Again, the experimental strategy is clear: for any gene of interest, one should require that multiple sgRNAs of different sequence give rise to the same phenotype in order to conclude that the phenotype is due to an on-target effect.

How Can It Go Wrong?

Even with optimized on-target design, and proper avoidance of off-target effects both explicitly when designing sgRNAs and experimentally by the use of multiple sgRNAs, it is apparent that not all genes are equally amenable to targeting in all cellular contexts. One major reason is the chromatin state of a target site. For genes that are in more restricted chromatin or, potentially, different locations in the nucleus, Cas9 will be less effective at finding the target (9). Achieving biallelic knockout of such a gene in a high percentage of target cells might therefore not be practical. Here, single cell-cloning might be necessary, and complementary technologies such as RNAi may be a better experimental choice (while still relying, of course, on multiple different sequences of small RNA to interpret a phenotype!)

In sum, selection of sgRNAs for an experiment needs to balance maximizing on-target activity while minimizing off-target activity, which sounds obvious but can often require difficult decisions. For example, would it be better to use a less-active sgRNA that targets a truly unique site in the genome, or a more-active sgRNA with one additional target site in a region of the genome with no known function? For the creation of stable cell models that are to be used for long-term study, the former may be the better choice. For a genome-wide library to conduct genetic screens, however, a library composed of the latter would likely be more effective, so long as care is taken in the interpretation of results by requiring multiple sequences targeting a gene to score in order to call that gene as a hit. Indeed, existing genome-wide libraries have not taken into account on-target activity, and new libraries will surely incorporate such design rules in the near future.

This is exciting time for functional genomics, with an ever-expanding list of tools to probe gene function. The best tools are only as good as the person using them, and the proper use of CRISPR technology will always depend on careful experimental design, execution, and analysis.

CRISPR/Cas9: Planning Your Experiment

How do I get started?

CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) genome editing is a popular new technology that uses a short RNA (gRNA) to guide a nuclease (generally, Cas9) to a DNA target. The technology has been quickly adopted due to its advantages, like speed, cost, efficiency, and ease of implementation, over protein-based targeting methods (zinc fingers and TALENs). This experimental guide is meant to provide a broad overview of the major steps and considerations in setting up a CRISPR experiment. With all genome engineering technologies, it is recommended that the user performs due diligence regarding off-target effects.

Before getting started, familiarize yourself with the science behind CRISPR at our CRISPR Science Guide. You can also find more information from our blog and our list of CRISPR forums and FAQs.

Experimental Design

1.Choose a CRISPR system

What do you want to use CRISPR for? Common uses of CRISPR are:

- Gene disruption (via insertion or deletion)

- Activation or repression of gene expression

- You can find more information about CRISPR uses in our CRISPR guide or browse CRISPR plasmids by function.

What system will you be using CRISPR in?

- You can browse CRISPR plasmids by model organism or browse CRISPR plasmids by function.

Once you know what you want to do and what system you want to use, you can design your gRNA.

2.Design a gRNA for your genome target

As versatile as the Cas9 protein is, it requires the specificity of a gRNA to guide it to the desired genome target. Choosing an appropriate target sequence in the genomic DNA is a very important step in designing your experiment.

Important characteristics of a genome target are:

- ~20 nucleotides in length

- Followed (or preceded) by the appropriate Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sequence in the genomic DNA

The PAM will vary depending on the bacterial species the Cas9 was derived from. The Cas9 and gRNA have to be from the same bacterial species. Read more about PAM sequences.

The majority of the CRISPR plasmids in Addgene’s collection are from the bacteria S. pyogenes unless otherwise noted.

gRNAs:

- should not contain the PAM sequence

- can be on either strand of the genomic DNA

For genomic disruptions (via Insertions/Deletions or InDels), the gRNA should be targeted closer to the N-terminus of a protein coding region to increase the likelihood of gene disruption.

For genome editing or modification, the gRNA target site will be limited to the desired location of the edit or modification.

- should be designed using bioinformatics software to minimize off-target effects

A gRNA sequence can potentially appear in multiple places in the genome.

While we offer validated gRNAs, there are a number of software tools available to help you choose/design target sequences, as well as lists of bioinformatically determined (but not experimentally validated) unique gRNAs for different genes in different species.

Looking for more help?

From our blog, John Doench and Ella Hartenian (Broad Institute) give practical advice for using CRISPRs, as well as designing your gRNA and introducing it into cells.

Additionally, we have gRNA design protocols from our CRISPR depositors and links to CRISPR discussion groups.

Once you have your genomic target identified and gRNA designed, you can synthesize the oligos for your gRNA and find an empty gRNA vector, or browse our selection of validated gRNAs.

- Clone the gRNA into a plasmid

If you are using one of our validated gRNA plasmids, you can skip this step.

If you have to clone your gRNA into your CRISPR plasmid:

- Depositor plasmids may have specific cloning guides in their protocols.

- For a general overview of cloning, review our molecular biology tools and references.

After cloning, sequence verify your final plasmid product. Some depositor tools are designed so that a test digest can verify a successful insertion.

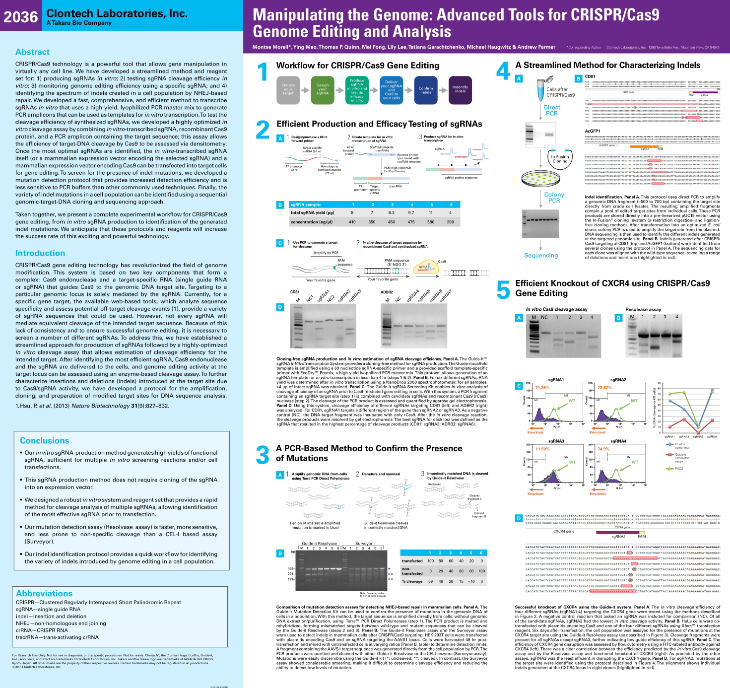

- Deliver your CRISPR components

Each model system will have its best practices for efficient delivery of CRISPR components. CRISPR depositors have submitted protocols for a few model organisms like nematode, fly, and zebrafish.

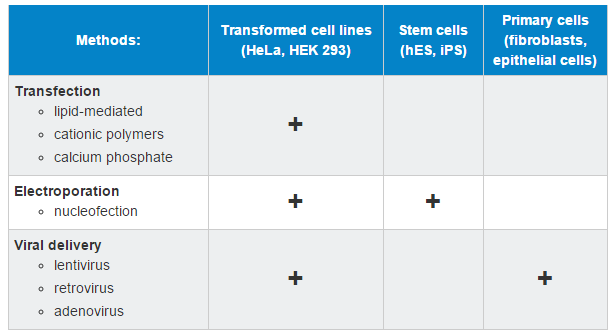

If you will be working in mammalian cell culture, some common mammalian DNA delivery methods are:

Mammalian Cell Line DNA Delivery

This table is not inclusive of all methods and the user will want to review the current literature about their preferred model.

- Evaluate outcome

If CRISPR is being used for genome modification, the modification has to be evaluated after delivery of CRISPR components.

- Design PCR (polymerase chain reaction) primers and amplify genomic region of modification.

PCR is a method for making a copy of a piece of DNA.

There are many software tools available on the web for primer design. Example: IDT Web Tools

View our walk-through of a basic PCR reaction and the required reagents.

- Two popular methods to assess genomic alteration from a PCR product are:

Endonuclease mismatch detection assay

NEB provides a graphical overview of the assay.

Sequence verification

Find tips for sequencing analysis and troubleshooting at our blog.

CRISPR-Cas9 FAQs Answered!

Designing Your CRISPR Genome Editing Experiment

Q1: Should I use wildtype or double nickase for my CRISPR genome engineering experiments?

A1: When assessing which nickase type to use for your CRISPR genome engineering experiments, consider that wildtype Cas9 with optimized chimeric gRNA has high efficiency but has been shown to have off-target effects. ‘Double nickase’ is a new system, developed by the Zhang lab, which has comparable efficiency to the optimized chimeric design but with better accuracy (in other words, lower off-target effect.

The double nickase system is based on the Cas9 D10A nickase described in Figure 4 of the Cong, et. al, 2013 Science paper. For example, if you want to use double nickase, you could express two spacers and use PX335 to express the Cas9n (nickase).

The concept of the double nickase system is that you can express two different chimeric gRNAs with the Cas9 nickase which will together introduce cleavage of the target site with efficiency similar to using a single chimeric gRNA. At the same time, the off-target effects are reduced because the Cas9 nickase doesn’t have the ability to induce double-stranded breaks like the wildtype Cas9 does. There are a few references for the double nickase system, including one recently from the Zhang group.

Learn more here.

Q2: When designing oligos for cloning my target sequence into a backbone that uses the human U6 promoterto drive expression, is it necessary to add a G nucleotide to the start of my target sequence?

A2: The human U6 promoter prefers a ‘G’ at the transcription start site to have high expression, so adding this G couldhelp with expression, though it is possible for the plasmid to still express without the G. Because the G is only one base, the Zhang lab usually adds it when they order the oligo. If your spacer sequence starts with a ‘G’, you naturally have one and do not need to add an additional ‘G’.

Q3: What is the maximum amount of DNA that can be inserted into the genome using CRISPR/Cas forHomologous Recombination (HR)? How long should the homology arms be for efficient recombination?

A3: The most we’ve tried to insert so far has been 1kb. We used homology arms that were 800bp long.

Tips for Using CRISPR-Cas9 at the Lab Bench

Q4: After the introduction of a mutation into the genome, how can cells with that mutation be selected/screened?

A4: Before starting your experiment, consider co-transfecting with GFP. This allows you to sort for GFP-positive cells and to enrich for those cells that were positively transfected. Alternatively, you can use a selection marker to select transfected cells (for example, plasmid with a puromycin resistance cassette, such as PX459). After you co-transfect the CRISPR/Cas system with your homologous recombination (HR) template, you could then:

- Confirm your HR by doing Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP) (see Figure 4 of the Cong, et. al, 2013 Science paper).

- If you detect positive HR, isolate single-cell colonies, grow them up, then perform individual genotyping (using Sanger sequencing, for example) on each colony in order to screen for positive ones.

- If your HR template has a selection marker such as puromycin, you can (also) select for the positive colonies by puromycin selection. You could then confirm this purification by performing a genotyping assay (such as Sanger sequencing).

Click herefor a useful reference.

More FAQS, CRISPR Protocols, and gRNA Design Tools

Need more questions answered about CRISPRs?

- Check out the full list of 16 FAQs answered by Le Cong

- Read Addgene’s CRISPR guide for background information on CRISPR/Cas9 systems

- Peruse the most recent genome editing review articles, such as: Sander JD & Joung JK, Nature Biotech, 2 March 2014.

- Or browse the articles related to the most frequently requested CRISPR plasmids at Addgene

Find protocols and gRNA design tools: - List of CRISPR protocols developed by a variety of labs and optimized for specific plasmids

- Links to different software to help you identify your gRNA target sequences

CRISPR/Cas9 文献

- Cell Press Selections: CRISPR/Cas9

- Science:A Swiss Army Knife of Immunity

- Science:A Programmable Dual-RNA–Guided DNA Endonuclease in Adaptive Bacterial Immunity

- Nature:Targeted mutagenesis in the model plant Nicotiana benthamiana using Cas9 RNA-guided endonuclease

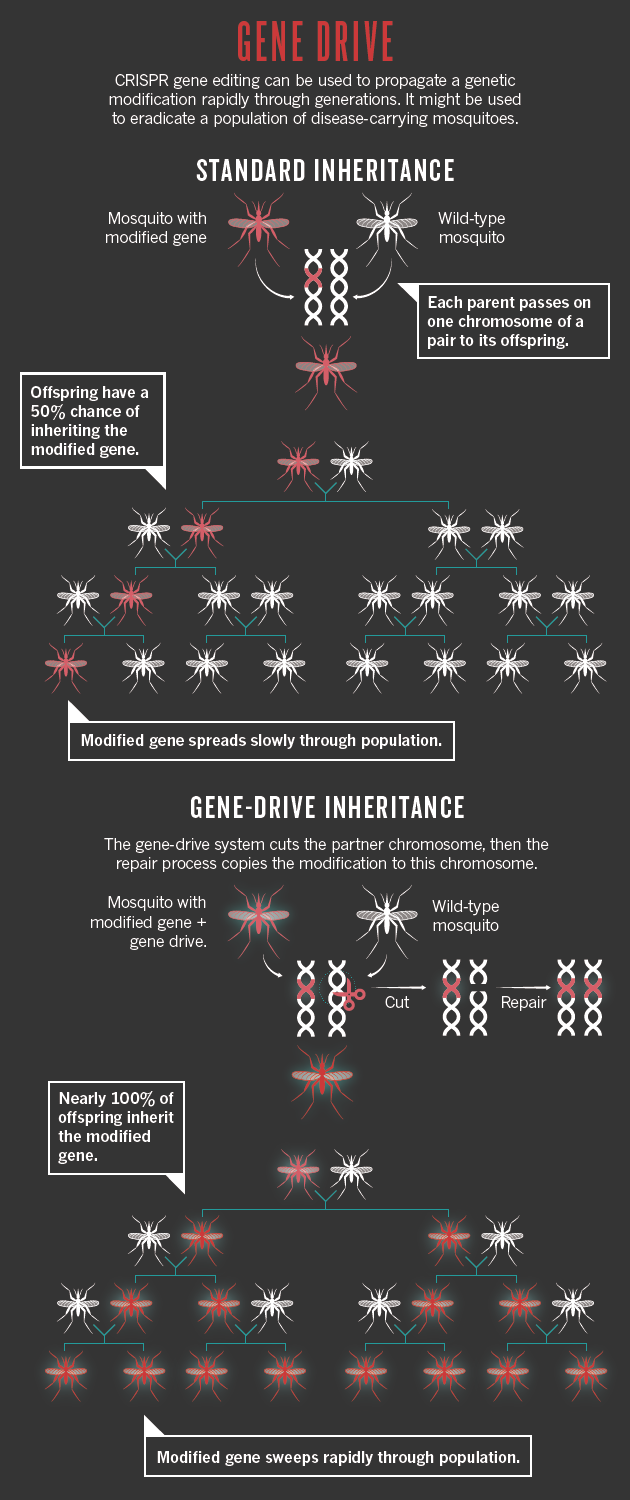

CRISPR/Cas9 科幻之力

◆ 自我复制

◆ 改变孟德尔遗传规律,改变整个种群